By Harriet Mallinson | Published on July 8, 2017

It’s easy to be sucked in by the smell of delicious food wafting over you. Pass a bakery in the morning at your peril.

It’s nothing new that being able to take pleasure in the aroma of what we are eating is key to enjoying food, but new research proves our sense of smell could have much more power over us than we previously thought.

Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, have found that being able to smell food may make us fatter while not being able to be smell may help us lose weight.

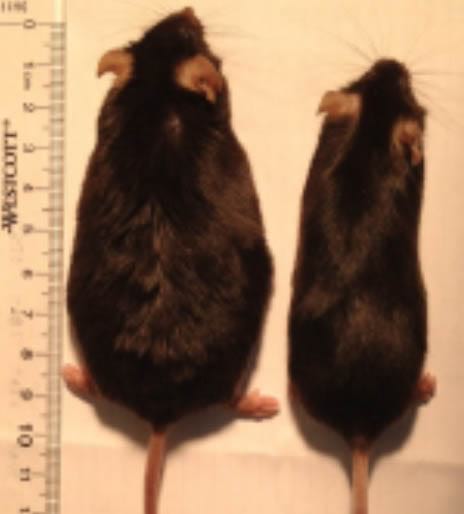

In an experiment using mice, researchers observed that obese mice whose sense of smell had been temporarily destroyed lost weight following a high-fat diet, while mice who retained their sense of smell – but ate the same amount of food – doubled in weight.

Furthermore, mice who’d had their sense of smell boosted got even fatter than the normal nice.

The findings suggest that the scent of what we eat may play an important role in how the body deals with calories. If you can’t smell your food, you may burn it rather than store it.

What’s the science behind it?

The results, published this week in the journal Cell Metabolism, point to a key connection between the olfactory or smell system and regions of the brain that regulate metabolism, in particular the hypothalamus.

“This paper is one of the first studies that really shows if we manipulate olfactory inputs we can actually alter how the brain perceives energy balance, and how the brain regulates energy balance,” says Céline Riera, a former UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow.

Humans who lose their sense of smell because of age, injury or diseases such as Parkinson’s often become anorexic, but the cause has been unclear because loss of pleasure in eating also leads to depression, which itself can cause loss of appetite. It is now apparent that the loss of smell itself plays a role.

– RELATED: Eating Late At Night Can Make You Gain Weight –

“Sensory systems play a role in metabolism,†says senior author Andrew Dillin. “Weight gain isn’t purely a measure of the calories taken in; it’s also related to how those calories are perceived.”

“If we can validate this in humans,†he adds, “perhaps we can actually make a drug that doesn’t interfere with smell but still blocks that metabolic circuitry. That would be amazing.”

Riera noted that mice as well as humans are more sensitive to smells when they are hungry than after they’ve eaten, so perhaps the lack of smell tricks the body into thinking it has already eaten.

While searching for food, the body stores calories in case it’s unsuccessful. Once food is secured, the body feels free to burn it.

The researchers used gene therapy to destroy olfactory neurons in the noses of adult mice so that the animals lost their sense of smell for about three weeks – before the olfactory neurons regrew thanks to spare stem cells.

After researchers temporarily eliminated the sense of smell in the mouse on the right, it remained a normal weight while eating a high-fat diet. The mouse on the left, which retained its sense of smell, ballooned up on the same high-fat diet.

The smell-deficient mice rapidly burned calories by up-regulating their sympathetic nervous system, which is known to increase fat burning.

The rodents turned their beige fat cells – the subcutaneous fat storage cells that accumulate around our thighs and midriffs – into brown fat cells, which burn fatty acids to produce heat. Some turned almost all of their beige fat into brown fat, becoming lean, mean burning machines.

Their white fat cells – the storage cells that cluster around our internal organs and are associated with poor health outcomes – also shrank in size. There was no effect on muscle, organ or bone mass.

Are there any negatives to such treatment?

A downside, however, was that the loss of smell was accompanied by a large increase in levels of the hormone noradrenaline, which is a stress response tied to the sympathetic nervous system. In humans, such a sustained rise in this hormone could lead to a heart attack.

Though it would be a drastic step to eliminate smell in humans wanting to lose weight, Dillin notes, it might be a viable alternative for the morbidly obese contemplating stomach stapling or bariatric surgery, even with the increased noradrenaline.

“For that small group of people, you could wipe out their smell for maybe six months and then let the olfactory neurons grow back, after they’ve got their metabolic program rewired,” Dillin explains.

“People with eating disorders sometimes have a hard time controlling how much food they are eating and they have a lot of cravings,” Riera says. “We think olfactory neurons are very important for controlling pleasure of food and if we have a way to modulate this pathway, we might be able to block cravings in these people and help them with managing their food intake.”

Harriet is Editor of MACROS and perfectly capable of eating an entire log of goat’s cheese in one sitting.